EU adopts new rules to significantly cut packaging waste with re-use targets

The European Union has formally adopted a regulation on packaging and packaging waste. The new ...

World leaders gathered this September to grapple with the global learning crisis at the UN’s Transforming Education summit. Bringing education to the top of the global political agenda, it’s a vital initiative.

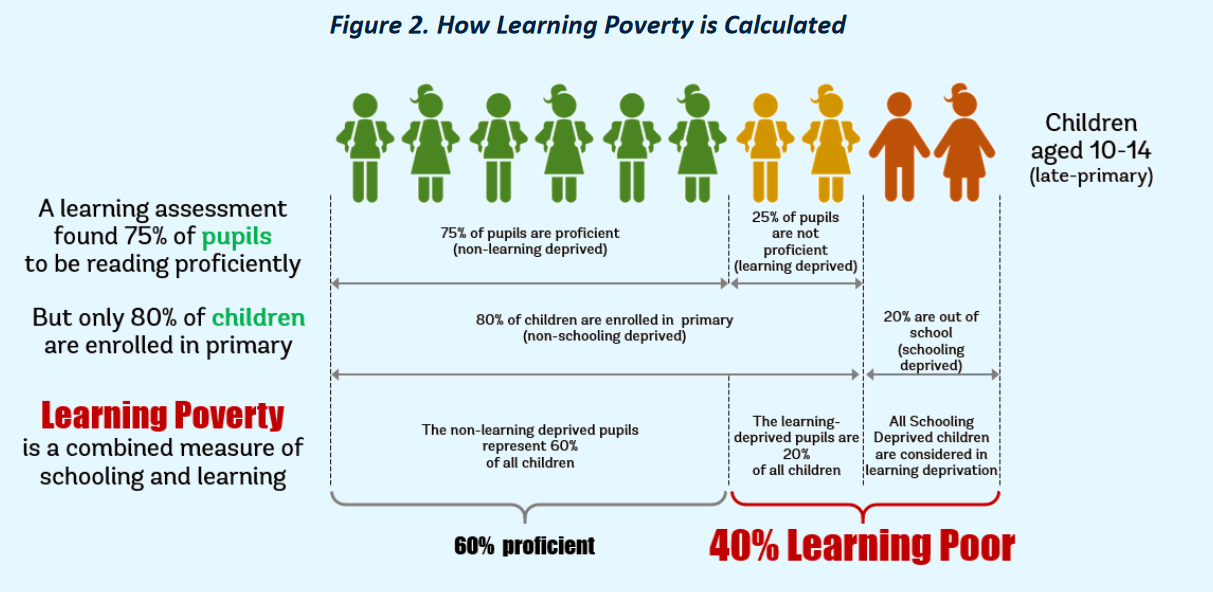

Even before the pandemic, the UN was warning the world was on course to miss out on SDG 4 goals. With 1.5 million learners impacted by school and university closures, COVID has made that mountain steeper still, especially in low- and middle-income countries where the rate of learning poverty has increased by a third. Pre-COVID, 57% of 10-year-olds in these countries were unable to understand a simple written text – today, it is 70%.

Global education – already in need of urgent reform – is tilting hard in the wrong direction. That world leaders recognize the need for transformative action is a step in the right direction, and I hope the legacy of this summit is lasting change. While talks are a start, what governments need to do is listen. They need to bring the teachers tackling the crisis at the ground level to the table and learn from the knowledge, experience and expertise bound up in our schools. This will help truly understand what needs transforming and how.

There’s much that can be learned from that famous – though unfortunately typical – story of a group of policy-makers discussing future roles for women in society back in the 1960s. The travesty of the situation was that no women were actually present. It took women many years and many protests, to get a seat at the table.

If world leaders aren’t ready to admit that they don’t have all the answers, that we can only begin to tackle the global education crisis if we listen to those on its frontlines, then educators at the coalface must raise their voices to be heard.

We launched the World’s Best School Prizes to provide schools with that platform: to surface their best practices and not only share them with their peers around the world for improving education from the grassroots but to show governments the everyday techniques that are changing children’s lives and how they might start systematizing what works.

Take just a few examples of this innovation from the schools we celebrated as our top three finalists this week.

Pinelands North Primary School in South Africa perfectly demonstrates the importance of inclusivity in education. When its principal took up the role in 1997, South Africa was emerging from the shadow of apartheid, and the student population of her school was still predominantly white. Today Pinelands is a beacon of diversity. All pupils, male or female, wear the same uniforms, kids are taught sign language, and the school has gender-neutral bathrooms. When the school accepted its first transgender pupil, it provided guidance for families about gender identities and trained staff to guide parents.

Meanwhile, Escuela Emilia Lascar, a school in Chile, shows that innovative solutions to engaging vulnerable students can have a significant impact. It launched its own “Emilia TV” programme broadcast weekly on social media to keep students motivated during the pandemic and beyond. Today, the school has its own TV studio producing student-led content on topical issues. The project led to increased enrolment and attainment.

We can take inspiration from schools like Dunoon Grammar School in Scotland, which curated new skill-based courses to turn around a brain drain impacting its rural community. This is a school that has not only changed its curriculum to meet the real-life needs of its students but tackled challenges in the wider community as well. Dunoon is a clear example of how strong schools build strong societies.

Their stories are many and varied, and they span the globe. But the results we repeatedly see in the world’s best schools are improved educational outcomes and stronger communities.

But the schools can’t do this alone – not sustainably. To truly maximize their expertise, creativity and impact, governments must understand what these schools are doing well and how to amplify their work.

When things don’t work, people and organizations either do more of what they were doing, thinking they can “power” their way through the problem, or they do less. Very few of them shift towards a different approach, but a shift is what we need, and no time has ever been more urgent than now.

If something comes out of this month’s talks at the Transforming Education Summit, let it be a recognition that lasting change for the better rarely comes solely from the top down. It is a multifaceted process in which mutual understanding, cooperation and collaboration are essential.

Even with the best will in the world, governments rise and fall, and education ministers come and go. Still, teachers are present day-in and day-out, striving to overcome often colossal challenges to improve the next generation’s lives.

Understanding how they are going about it is not just a study in effective pedagogy. It’s the true art of policy-making.

The European Union has formally adopted a regulation on packaging and packaging waste. The new ...

Inaugurating the Abydos Solar Power Plant in the Upper Egypt governorate of Aswan represents a ...

Businesses that fail to adapt to climate risks like extreme heat could lose up to ...

اترك تعليقا