Sweden pledges extra $19m in Loss and Damage Fund

Sweden pledges additional $19 million to the Loss and Damage Fund at the 29th United ...

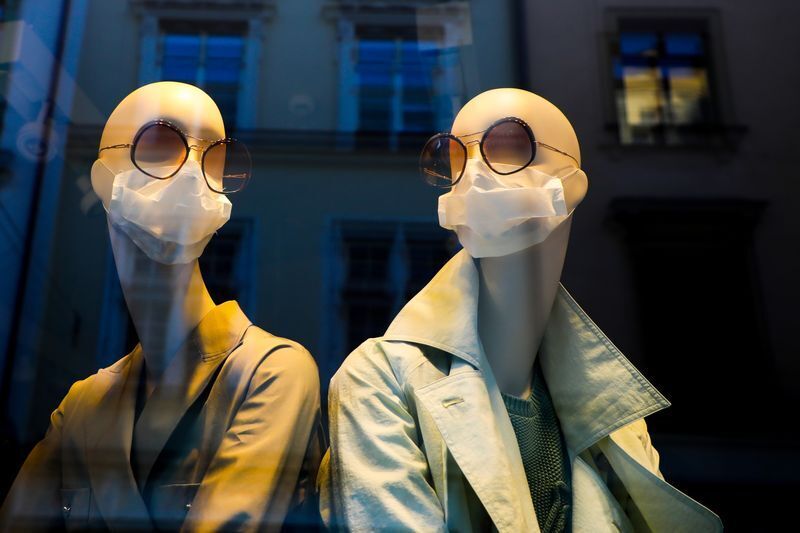

Coronavirus lockdowns have forced giants such as Primark, H&M, and Zara-owner Inditex to shut down thousands of shops and cancel orders worth millions of dollars. In the coming months, the fashion industry will face a “Darwinian shakeout” that will put 80% of companies in Europe and the U.S. in financial distress, according to a Mckinsey report from April. Yet one corner of the market is thriving.

“We are doing better this month than we did during Christmas,” says Cora Hilts, founder and chief executive officer at Reve en Vert, a platform selling luxury fashion focused on sustainability. “People are shopping more online and have more time to make conscious decisions. Our designers have greater control over the supply chain because it’s very difficult to produce abroad and be sustainable.”

Large retailers source textiles to third parties in developing nations such as China, Vietnam or Bangladesh, says Kirsi Niinimaki, a design professor at Aalto University in Finland. These elements are often made by under-paid workers operating old, energy-intensive machinery, treated with polluting chemicals banned in developed countries.

“Shorter supply chains allow for more transparency,” Niinimaki says. “For most brands we still don’t know where things are produced, using which chemicals and what waste comes out. That’s quite problematic.”

Niinimaki co-authored a scientific review published in Nature earlier this year showing that the sector produces around 20% of the world’s wastewater—mainly through treating or dyeing fabric—and the plastic microfibers used in many garments release the equivalent of 50 billion plastic bottles into the oceans each year. The rise of fast fashion, which depends on shoppers buying cheap items frequently, only makes things worse. At a time when even oil majors are trying to cut greenhouse gas emissions, those from the fashion industry are expected to surge by more than 50% by 2030. The solution is to transition to a “slow fashion” model, the review concluded.

The European Union is still drafting its economic recovery plan, but policymakers in several nations are already calling for measures that push for shorter supply chains to ensure manufacturing of critical components in the region. Stimulus packages targeting local small and medium companies could disproportionately affect green fashion businesses, Niinimaki says, giving them a further leg up in the future economic recovery.

“Stimulus packages should be going to small companies who are operating in an ethical way,” Hilts says. “It would be good to assign funds to companies who are producing sustainably, employing teams of conscious and skilled workers, and are operating locally.”

The fashion industry is so fragmented that just calculating the environmental impact of making a t-shirt is a challenge. A September report by the United Nations Development Program and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation estimated that fashion is the world’s second-largest polluter and responsible for about 10% of annual global carbon emissions, more than all international flights and maritime shipping combined.

Transparency is a struggle for the brands, which often don’t know where their products are at any given time, says Niall Murphy, chief executive officer at Evrythng, a platform providing product tracing and analytics services to fashion firms. The pandemic has exacerbated the problem.

“A producer might have thought they were fine, onshore producing in EU, but then it turns out their production was dependent on the supply of a material that was disrupted,” Murphy says. “The crisis has shown there are real resilience issues in supply chains.”

Among its conclusions, the McKinsey report said that post-virus supply chains will have to shrink to avoid essential products being stranded for months in distant ports in case of new virus outbreaks and lockdowns. That should reduce emissions from transport and improve environmental control over factories.

Most fashion brands are now completely paralyzed due to the lockdowns, so addressing these issues and fulfilling pre-pandemic environmental commitment will probably become part of the strategy after economies—and shops—reopen. But some have already been forced to tackle these issues.

French wool and textile manufacturer Chargeurs SA shifted some of its production lines from fabrics and garments to equipment for medical workers. In a matter of weeks, it has become one of the French government’s main provider of protective face masks and manufactures several million a week. Now the company is planning to shift production lines in its U.S., Asian, and South American factories, too, rather than shipping masks to those places all the way from France, says Angela Chan, the company’s global president and managing director for fashion technologies.

“Right now everything is at a halt, people are just trying to get through this,” Chan says. “But this is a corrector for the industry that will push us to think differently. It will put sustainability on top of everyone’s minds.”

Sweden pledges additional $19 million to the Loss and Damage Fund at the 29th United ...

New Chief Executive Officer (CEO) DHL Express in the Middle East and North Africa(MENA) Abdulaziz ...

Lindt & Sprüngli has already achieved a reduction in its carbon footprint in transportation, with ...

اترك تعليقا